Change in Mental Health After Smoking Cessation Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

Summary

Smoking rates in people with depression and anxiety are twice as high as in the general population, even though people with low and anxiety are motivated to stop smoking. Nigh healthcare professionals are enlightened that stopping smoking is ane of the greatest changes that people can make to improve their health. All the same, smoking abeyance can be a hard topic to heighten. Prove suggests that smoking may cause some mental health problems, and that the tobacco withdrawal cycle partly contributes to worse mental health. Past stopping smoking, a person's mental health may improve, and the size of this improvement might be equal to taking antidepressants. In this article we outline ways in which healthcare professionals can compassionately and respectfully raise the topic of smoking to encourage smoking abeyance. We draw on evidence-based methods such as cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) and outline approaches that healthcare professionals can use to integrate these methods into routine care to help their patients stop smoking.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this commodity you volition be able to:

-

• use principles from CBT to help people with common mental health problems to understand how their tobacco dependence and mental health are linked

-

• empathise how the tobacco withdrawal cycle, conditioned craving and possible increases in side-effects of prescribed medications on cessation tin all mimic the symptoms of mutual mental health problems such as anxiety, depression, low mood or stress

-

• empathise how breaking the tobacco withdrawal cycle, better coping with cravings and developing greater self-command can all amend mental health.

This guide is for healthcare professionals who are involved in routine healthcare for people who take common mental health problems such as anxiety, depression, low mood or stress, and who fume tobacco. They might be nurses, psychological well-being practitioners, psychiatrists, general practitioners, therapists or clinical psychologists, working in whatsoever healthcare setting where in that location is the opportunity to offer a brief or intensive behavioural intervention to encourage or support smoking abeyance. Practitioners practise not demand to exist experts in tobacco addiction or CBT to utilise, read or apply this review and guide. Although the focus of this article is primarily on those with common mental health bug, it may also be a useful guide in consulting with patients who report stress and other mood disturbances.

Background

Smoking tobacco is the globe'south leading cause of preventable illness and death (World Health Arrangement Reference Weinberger, Platt and Copeland2011). One in every 2 smokers will die of a smoking-related disease, unless they stop smoking (Doll Reference Doll, Peto and Boreham2004; Pirie 2013). In the UK, smoking prevalence has decreased from 46% during the 1970s to about fourteen% in recent years (Function for National Statistics 2020). However, approximately 34% of people with low and 29% of people with anxiety in the Uk smoke tobacco (Taylor Reference Taylor and Munafò2020a). People with depression and anxiety are more heavily addicted, suffer from worse withdrawal (Regal Higher of Physicians Reference Rabin, Ashare and Schnoll2013) and observe it harder to quit (odds ratio 0.81, 95% CI 0.67–0.97) (Hitsman Reference Hitsman, Papandonatos and McChargue2013). These inequalities at least partly contribute to a reduction in life-expectancy in people with mood disorders when compared with the general population (mortality rate ratio ane.92 (95% CI 1.91–1.94) (Plana-Ripoll Reference Parrott2019).

Most healthcare professionals are aware that stopping smoking is 1 of the greatest changes that people can brand to improve their health. All the same, smoking cessation tin can be a difficult topic to raise. Many people say that smoking tobacco helps them to convalesce stress, cope with mental health difficulties such equally low mood or anxiety and that smoking brings them relaxation or pleasure (Malone Reference Lapshin, Skinner and Finkelstein2018; Taylor Reference Taylor, Sawyer and Kessler2020b). When discussing smoking cessation, healthcare professionals tin can sometimes feel that they might be depriving people of one of their pleasures or power to cope with stress. They can also feel that they might undermine their relationship with patients and the patients' trust, which could compromise time to come consultations and treatment plans (Sheals Reference Sheals, Tombor, McNeill and Shahab2016).

Traditionally, tobacco habit and mental illness have been treated separately, usually focusing on mental illness get-go (Bakery Reference Bakery, Denham, Pohlman, Badcock and Paulik2019). Inquiry shows that people with mental wellness bug are as motivated to quit every bit the general population, with more than half contemplating quitting inside half dozen months, or preparing to quit within 30 days (Richardson Reference Plana-Ripoll, Pedersen and Agerbo2019). However, for many people, mental health weather condition can exist recurring over the longer term. So, when is 'the correct time' to quit smoking? People with mood disorders are most likely to die from smoking-related diseases (Plana-Ripoll Reference Parrott2019). How best can healthcare professionals address smoking cessation when their main presenting concern is the patient'south mental health?

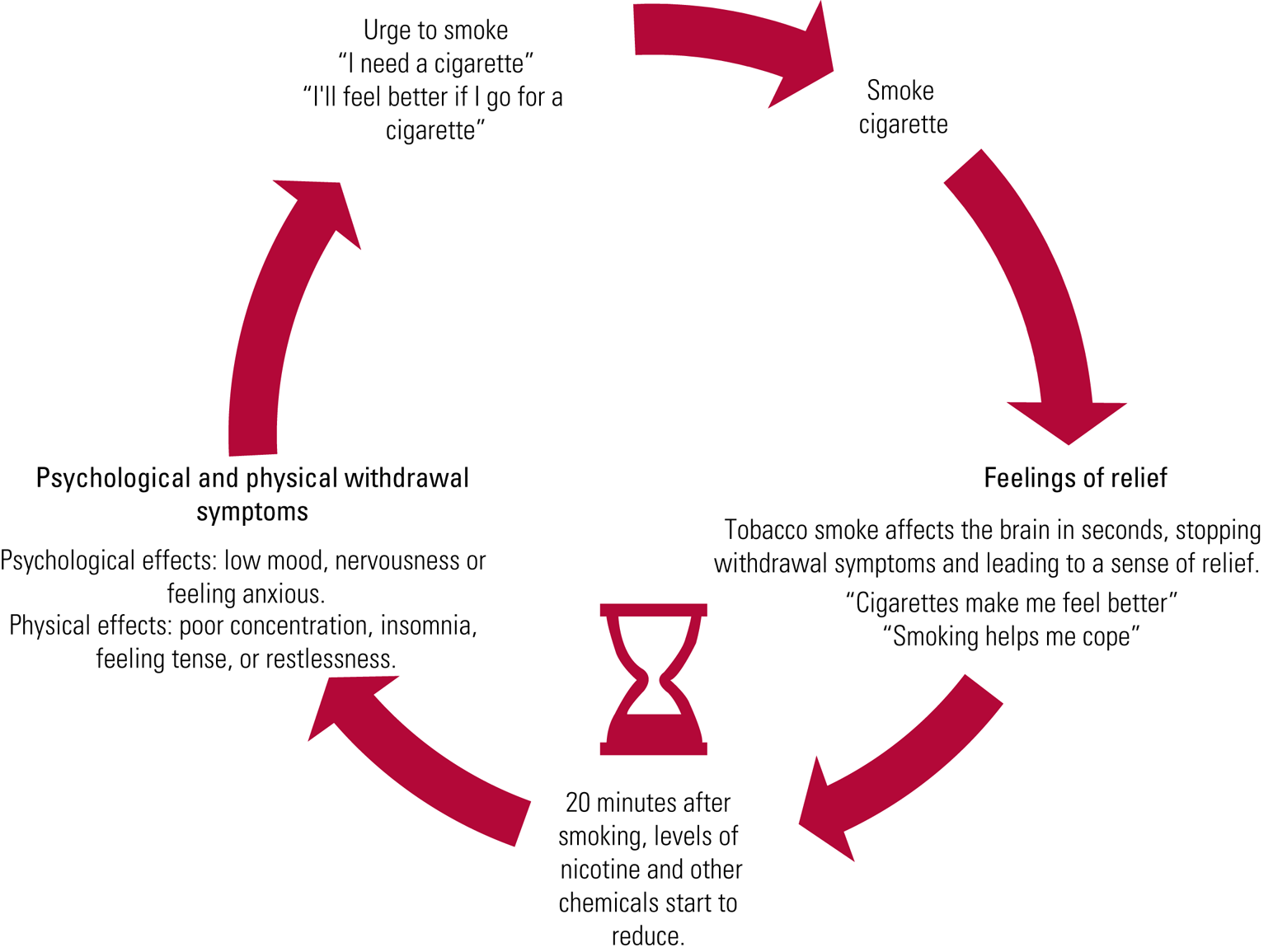

Information technology is not yet widely known that smoking tobacco might actually cause mental health issues (Taylor Reference Stevenson, Oliver and Hallyburton2019a) and that stopping smoking may improve mental wellness (Taylor Reference Segan, Bakery and Turner2014, Reference Taylor, Aveyard and Bartlem2020c). In fact, the size of improvement in mental wellness observed when people stop smoking is similar to the size of consequence observed when people take antidepressants (Taylor Reference Segan, Bakery and Turner2014). This comeback can be at least partly explained by breaking the tobacco withdrawal cycle. Tobacco addiction leads to periods of withdrawal presently after having a cigarette, whereby the person experiences psychological symptoms such as low mood, feet, poor concentration and irritability (Benowitz Reference Benowitz, Hukkanen, Jacob, Henningfield, London and Pogun2010). If the person smokes on a regular basis they will feel these withdrawal symptoms much of the fourth dimension, with brusque periods of relief but while they smoke and shortly after.

In that location are ways that healthcare professionals can compassionately approach smoking abeyance and remain respectful of the patient'south autonomy. Information technology is of import to share new research findings, reassuring patients that stopping smoking will not take a negative impact on their overall mental health and could actually improve mental wellness in the long term. This cognition could empower patients and motivate smoking cessation. Smoking abeyance treatments are effective in people with mental health issues (Taylor Reference Taylor and Munafò2020a). However, as people with mental health problems often feel college levels of tobacco dependence, they can crave college doses over longer periods of time of some smoking cessation medicines, such as nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) (NCSCT 2019; NICE 2020), and tailored behavioural support during their quit attempt (Nice Reference Miller and Rollnick2013; NCSCT 2019) specifically targeting mood (van der Meer Reference Taylor, Itani and Thomas2013).

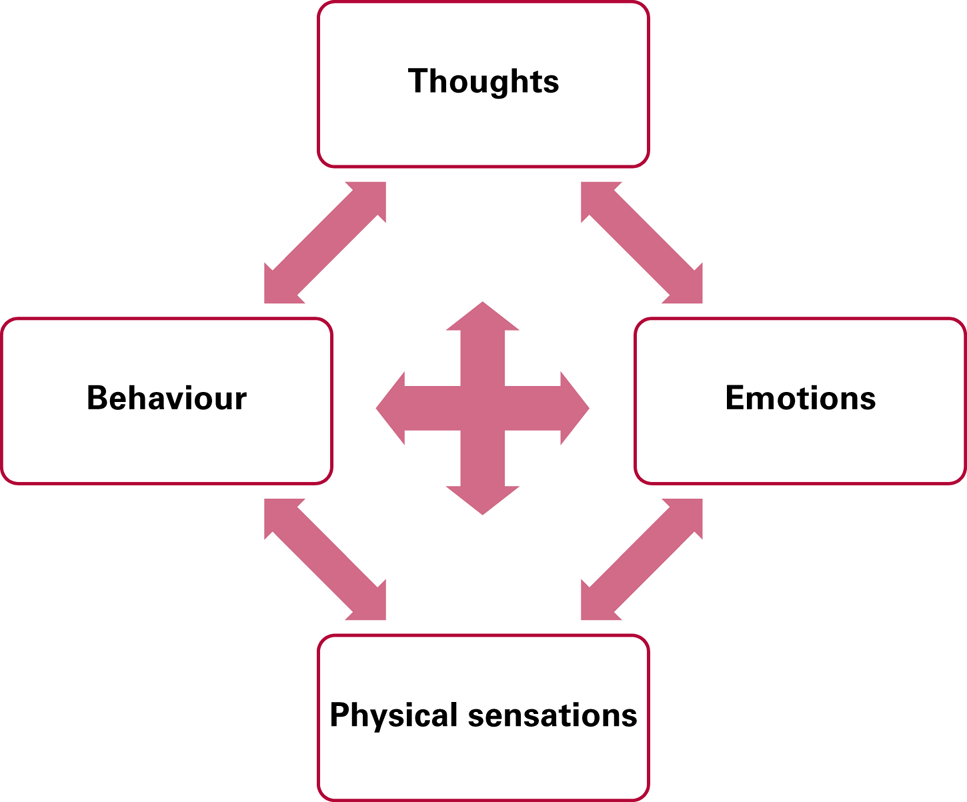

Understanding cognitive–behavioural therapy principles

The basic principles of cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) are a useful way to help patients to see how their thoughts, emotions, behaviour and physical sensations are interlinked (Fig. 1). CBT is usually used to treat conditions such as anxiety, depression, low mood and stress, but can also be used to care for smoking, booze and other drug problems. Recently, a dual process theory of addiction has been proposed, whereby addictive behaviour is the upshot of the predominance of implicit, automatic and mainly not-witting cognitive processes over explicit, controlled and mainly conscious processes (Heather Reference Heather, Segal, Heather and Segal2016). CBT helps people focus on their present challenges and how these are linked with their thoughts, emotions, behaviour and physical sensations. Using this model can assistance people to recognise, assess and respond to their bug, by establishing greater behavioural and cognitive control over impulsive urges and preventing relapse (Heather Reference Heather, Segal, Heather and Segal2016).

FIG 1 Tobacco addiction maintenance cycle.

Linking mood and other mental health symptoms with smoking using a CBT model

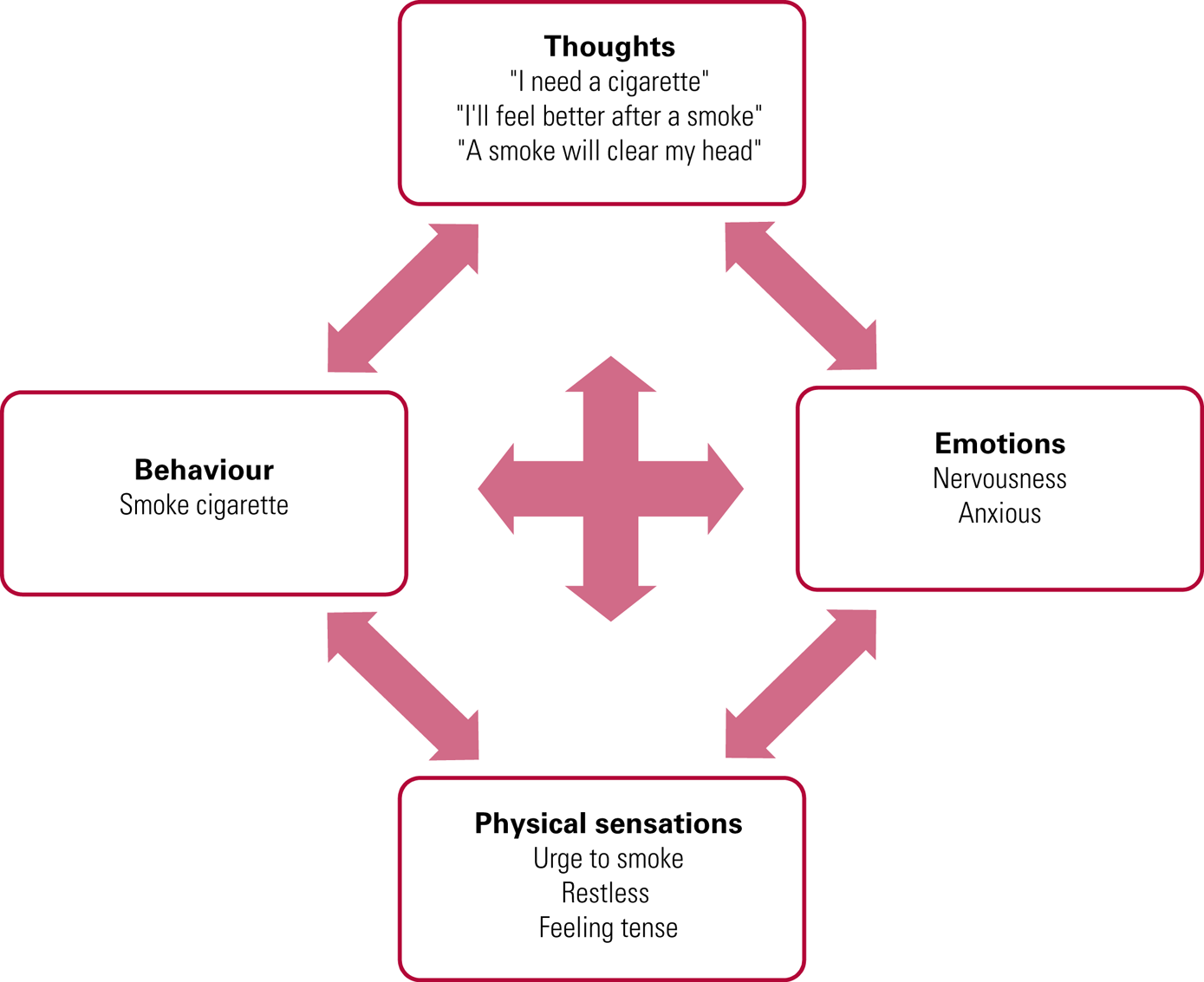

Using a CBT model can likewise be used to help people to run across how their thoughts, emotions, behaviour and physical sensations are interlinked in the context of their tobacco dependence and mental health (Fig. 1). To promote smoking cessation for people with depression or feet, self-monitoring of mental health symptoms and medication side-effects increases understanding about their links. Monitoring that starts pre-cessation and continues for a few weeks post-cessation may aid to distinguish temporary nicotine withdrawal symptoms from a relapse of mental illness and, for those taking medication, can track common agin side-effects that can increase with quitting (Segan 2017). Of form, monitoring can too help to address symptoms regardless of their cause.

One such monitoring tool, used by Quitline Victoria (Segan 2017), is outlined in Box ane. It includes the 8-item Minnesota Nicotine Withdrawal Scale (Hughes Reference Hughes2007a), which is referred to as a 'mood and experiences scale' because smokers might be confused by completing a 'withdrawal' scale prior to abeyance and sometimes, mail-cessation, may not report a symptom if they do non believe that it is due to withdrawal. The term 'symptom' is likewise avoided, every bit it is very clinical and tin imply that something is wrong and needs fixing; instead, the phrases 'moods and experiences' and 'possible side-effects' are used.

BOX 1 The Quitline Victoria smoking cessation monitoring tool

Structured monitoring of:

-

(a) nicotine withdrawal symptoms or 'mood and experiences' (Segan Reference Segan, Bakery and Turner2017), using the 8-particular Minnesota Nicotine Withdrawal Calibration (Hughes Reference Hughes2007a):

-

• anger/irritability/frustration

-

• anxiety or nervousness

-

• low/sad mood

-

• desire/craving to smoke

-

• difficulty concentrating

-

• increased appetite/hunger/weight gain

-

• indisposition/sleep problems/enkindling at night

-

• restlessness/impatience

-

-

(b) the well-nigh common adverse side-effects of psychiatric medications (Lapshin Reference Kay-Lambkin, Edwards and Bakery2006), or 'possible side-effects' (Segan Reference Segan, Baker and Turner2017):

-

• dry mouth or increased salivation

-

• increased thirst

-

• headache

-

• nausea

-

• drowsiness, tiredness, fatigue

-

• increased sleep

-

• blurred vision

-

• dizziness

-

• increased sweating

-

(Segan 2017)

In the example of feet, depression, low mood and stress, the 5 areas of the CBT model tin aid us understand that these weather and their associated feelings can be a trigger for smoking. People written report smoking in an effort to calm themselves down, reduce anxiety, make themselves feel relaxed, give themselves a break or to cocky-medicate. As smoking provides short-term relief from withdrawal, and as the person thinks they experience better later a cigarette, this reinforces their smoking behaviour. Still, as piddling as 20 minutes after smoking a cigarette this cycle will happen again (Benowitz Reference Benowitz, Hukkanen, Jacob, Henningfield, London and Pogun2009), generating further feelings of anxiety, sadness, hopelessness and so on. Figures 2–4 show how these areas interact with one another to maintain an unhelpful coping behaviour or maintain a design of low mood or anxiety. An blitheness by the Habit and Mental Wellness Group (AIM) available at https://youtu.be/HiYBGOQ-PIo summarises this approach. Another animation past AIM available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iQn4MbWbiSU, almost the tobacco withdrawal bicycle, might be a useful tool when explaining links between tobacco use and depression/anxiety symptoms to patients.

FIG 2 Reinforcement of smoking behaviour: the cognitive–behavioural model.

FIG iii The anxiety cycle in smoking: the trigger is an anxiety-provoking event.

Integrating CBT principles for smoking and mental health into routine intendance

These CBT principles are designed to be used as a tool, not as a sole treatment, and are best used equally office of a recommended smoking cessation treatment. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2018), for example, recommends behavioural support in combination with pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation. Depending on time available and circumstances, support might be very brief advice or more in-depth behavioural back up; or it might involve developing a collaborative model or 'formulation' of the person'due south smoking and a plan for cerebral and behavioural change involving such approaches as behavioural activation, mindfulness, coping with cravings and relapse prevention. Pharmacotherapy choice volition depend on previous experience, preference and whether or non the person will too consult a medical practitioner for a prescription. Pharmacotherapy includes nicotine replacement therapy (unremarkably a combination of nicotine patches and one or more curt-acting forms such as glue, lozenges, spray or vaporiser), varenicline or bupropion (depending on land). Smokers may also want to effort e-cigarettes equally a nicotine replacement production, which is supported by Public Health England (McNeill Reference McNeill, Brose, Calder, Bauld and Robson2020). Adherence to medications is important and this tin be monitored forth with mood and experiences to enhance discussion of how smoking abeyance medication helps to convalesce withdrawal.

Very brief advice for smoking cessation

The 'very cursory advice' approach recommended past the National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training (NCSCT) is being increasingly used (Box 2). A systematic review and meta-analysis of brief opportunistic interventions for smoking abeyance found that healthcare professionals tin be more constructive in promoting attempts to stop smoking by offering aid to all smokers, rather than offering assistance only to those who state that they desire to finish smoking (Aveyard Reference Aveyard, Begh and Parsons2012). Brief interventions in settings such equally primary care tin can be very effective in improving lifestyle behaviours (Aveyard Reference Aveyard, Lewis and Tearne2016).

BOX ii Very cursory communication (the three A'south)

Ask – establish smoking condition: 'Practice you smoke tobacco cigarettes or roll-ups?'

Advise – that the best fashion of stopping smoking is to use a combination of behavioural back up and drug handling: 'Did you know that smoking cessation medicine plus smoking abeyance counselling tin can double your chances of quitting?'

Act – provide a referral or offer behavioural back up using the CBT model equally a tool, and follow-upwards appointments: 'Would you like to meet once again to talk almost smoking cessation options?', 'I tin refer you to a smoking cessation specialist, if you similar?'

(Aveyard Reference Aveyard, Begh and Parsons2012; NCSCT 2020)

Smokers may say that they are 'too stressed out to stop', that they would similar to 'deal with their mental health problem before they finish smoking', or that they 'won't be able to cope without cigarettes'. This may exist an ideal opportunity to implement the CBT principles for smoking and mental wellness (Figs 1–iv) to explore their mental health and tobacco dependence. This might encourage them to retrieve about stopping smoking or even prompt a quit attempt.

Standard behavioural support for smoking cessation

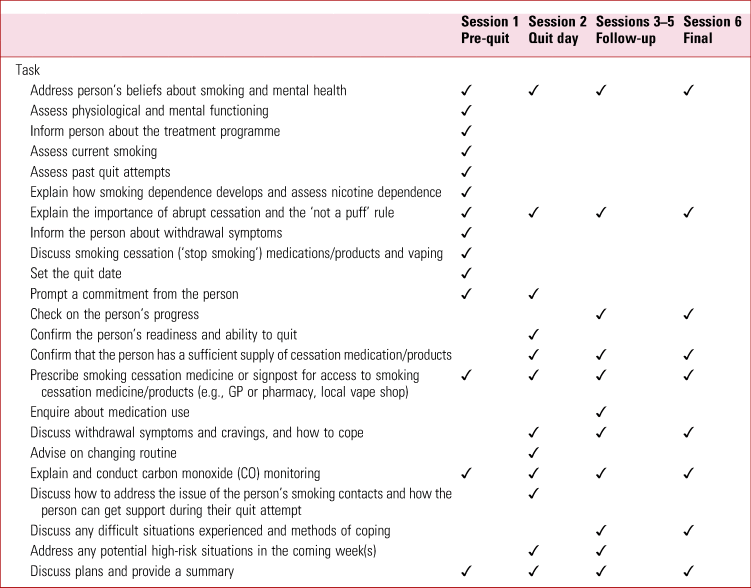

For healthcare professionals who are regularly consulting with the person, are involved in offering behavioural support to change lifestyle behaviours, or in the provision of behavioural back up for smoking cessation, the CBT principles for smoking and mental health discussed hither can be integrated into the standard smoking cessation treatment program designed past the NCSCT (2019). For example, the NCSCT recommends that standard behavioural back up for smoking abeyance involves of 110 minutes of behavioural back up over half-dozen sessions. During each of these sessions, in that location are opportunities to provide support for whatsoever concerns the person is having about quitting smoking and their mental health, psychoeducational opportunities about the withdrawal cycle and mental health, and explaining the mental health benefits of smoking cessation.

In the ESCAPE trial (Taylor Reference Taylor, McNeill and Girling2019b), psychological well-being practitioners are integrating smoking cessation treatment into psychological services for common mental health problems, using a smoking cessation intervention checklist (Table 1). Using this checklist, they are tailoring the intervention content to the person's needs. Psychological well-existence practitioners dedicate fourth dimension during each session to accost the person's beliefs about smoking and mental wellness, and tailor intervention components using their knowledge virtually smoking and mental wellness, and mental wellness and tobacco withdrawal.

Tabular array one National Center for Smoking Cessation and Preparation standard handling programme with boosted mental health support for smoking abeyance

Understanding links between tobacco utilise and mental health bug

When someone starts smoking, there are some rewarding furnishings of tobacco on mood and cognition. Social reasons, such as feelings of belonging, tin besides be important. Smoking is also used equally an appetite suppressant. Nonetheless, as the person becomes used to the effects of tobacco, these reasons for smoking tend to diminish as the alleviation of withdrawal symptoms such as low mood, irritability, poor concentration, restlessness and anxiety gain prominence (Benowitz Reference Benowitz, Hukkanen, Jacob, Henningfield, London and Pogun2010; Hughes Reference Hughes2007b). Nevertheless, the initial rewarding effects of smoking tend to remain of import in the minds of smokers and it is these rewards that can tempt them back to smoking, even long after abeyance has been accomplished (Stevenson Reference Schauer, King and McAfee2017).

Regular smoking causes neuroadaptations in nicotinic pathways in the brain. Neuroadaptations in these pathways are associated with occurrence of depressed mood, agitation and anxiety shortly afterward a cigarette is smoked (Benowitz Reference Benowitz2009). This withdrawal cycle is marked by fluctuations in a smoker's psychological state throughout the day and tin can worsen mental health (Parrott 2004). There is prove that some systems that are compromised during longer-term tobacco exposure recover after smoking cessation (Mamede Reference Malone, Harrison and Daker-White2007).

People who smoke regularly will experience these withdrawal symptoms much of the fourth dimension, with short periods of relief merely while they fume and before long after (Fig. iv). When defenseless in this cycle, people tin mistakenly believe that smoking helps save symptoms of anxiety, depression, low mood or stress (Parrott 2004). But this is not the case – these symptoms are caused by tobacco withdrawal. Stopping smoking will eventually alleviate these symptoms altogether. Improvements in these symptoms commonly start several weeks after stopping smoking, and then the bike is broken (Taylor Reference Segan, Bakery and Turner2014). Lapses in cessation can be associated with recalling the initial pleasures associated with smoking or behavior nearly dealing with stress. Lapses tin can exist seen equally learning opportunities towards eventual cessation.

FIG four The depression cycle in smoking: the trigger is feeling depressed at dwelling house in the evening.

Tobacco use is a savage cycle that can negatively affect mental health. It is useful to explain this cycle to smokers with mental health problems, to help them sympathise how their smoking and mental health are linked. This information can be formulated as office of their presentation and a clear understanding can be sought near how smoking can get a maintenance gene in their mental health difficulties. Figure 1 shows that 20 minutes after smoking a cigarette, levels of nicotine and other chemicals first to reduce (Benowitz Reference Benowitz2009). This leads to physical and psychological tobacco withdrawal with symptoms such as poor concentration, indisposition, feelings of tension, restlessness, low mood and anxiety. It is easy to see how most of these symptoms might be mis-attributed as symptoms of mental illness.

Can smokers cope without tobacco?

In that location are many reasons why people report smoking tobacco. People with mental wellness problems commonly report smoking cigarettes to alleviate emotional problems and feelings of depression and anxiety, to stabilise mood, and for relaxation and stress-relief (Malone Reference Lapshin, Skinner and Finkelstein2018).

Studies take followed people making a quit attempt and show that when they stop smoking their mental wellness improves and, conversely, when they relapse, their mental health worsens to where information technology was before (Taylor Reference Segan, Baker and Turner2014). Similarly, there is proficient testify that taking up smoking early on in adolescence is associated with developing low and anxiety (Wu Reference Westward, Kale and Brown1999; Jamal Reference Humfleet, Muñoz and Sees2011, Reference Jamal, Does and Penninx2012).

Smoking cessation tin increment the blood levels, and hence side-effects, of some psychotropic medications as well equally alcohol and caffeine (Segan 2017). This is because the tar in cigarette smoke (not the nicotine) causes the body to interruption down some substances more than quickly than usual. Nicotine and nicotine replacement therapies do not bear upon medication, caffeine or alcohol levels in this style. Monitoring these side-effects with the person quitting smoking can exist helpful and we depict how to exercise so in Box i.

Will stopping smoking damage mental health?

Stopping smoking volition non harm mental health. Evidence to engagement suggests that in that location may exist a causal upshot of smoking on mental illness, such that starting smoking increases risk of low, schizophrenia (Taylor Reference Stevenson, Oliver and Hallyburton2019a) and bipolar disorder (Vermeulen Reference Vermeulen, Wootton and Treur2019). A systematic review and meta-analysis of 26 longitudinal studies institute that stopping smoking was also associated with long-term improvements in mental health similar in result size to taking antidepressants, and the benefit was at least every bit large in people with psychiatric conditions (Taylor Reference Segan, Baker and Turner2014). Another study plant no consequent prove that varenicline, an effective medicine for smoking cessation, was associated with greater odds of depression, neurotic disorder, antidepressant or hypnotic/anxiolytic prescription in people with or without mental disorders (Taylor Reference Taylor and Munafò2020a). In general, this study institute that varenicline was associated with improved mental wellness outcomes, such every bit reductions in antidepressant and anxiolytic prescriptions up to 2 years later on taking medicine to stop smoking (Taylor Reference Taylor and Munafò2020a).

What well-nigh patients with comorbid mental health issues, tobacco dependence and substance/booze use?

In people with comorbid substance and/or alcohol utilise, smoking rates are more than than double those in non-users with similar demographic characteristics (Guydish Reference Guydish, Passalacqua and Pagano2016). Importantly, many people who use substances and/or alcohol and who smoke tobacco are motivated to quit smoking tobacco, but written report lack of support (Gentry Reference Gentry, Craig and Kingdom of the netherlands2017).

Some studies prove that cannabis co-apply is associated with worse tobacco-smoking cessation outcomes, compared with tobacco-only employ (Abrantes Reference Abrantes, Lee and MacPherson2009; Schauer Reference Richardson, McNeill and Brose2017; Vogel Reference Van Zundert, Kuntsche and Engels2018; Weinberger Reference Vogel, Rubinstein and Prochaska2018; McClure Reference Mamede, Ishizu and Ueda2019). Yet, other studies show that cannabis employ is not associated with tobacco abeyance outcomes (Humfleet Reference Hughes1999; Hendricks Reference Hendricks, Delucchi and Humfleet2012; Rabin Reference Pirie, Peto and Reeves2016). Similarly for alcohol, co-utilize is associated with worse smoking cessation outcomes compared with tobacco-merely use (Humfleet Reference Hughes1999; Van Zundert Reference Taylor, McNeill and Farley2012; Haug Reference Haug, Schaub and Schmid2014, Reference Haug, Paz Castro and Kowatsch2017; Weinberger Reference Verplaetse and McKee2017); alcohol employ is also associated with increased tobacco cravings, and vice versa (Cooney Reference Cooney, Litt and Cooney2007; Verplaetse Reference van der Meer, Willemsen and Smit2017). People with alcohol or opioid dependence report several barriers to quitting smoking tobacco, including feet, tension/irritability and concerns about the ability to maintain abstinence from their principal substance of misuse (McHugh Reference McClure, Bakery and Hood2017). Those who study more barriers to smoking cessation while using substances or alcohol report depression conviction in the ability to change their tobacco-smoking behaviour (McHugh Reference McClure, Baker and Hood2017).

Historically, substance/booze use and tobacco dependence are treated separately. However, more recently, there has been a motion towards interventions that target multimorbidity, including dual tobacco and substance/booze use, in people with mental disorders (Kay-Lambkin Reference Jamal and AJ2013; Bakery Reference Baker, Kavanagh and Kay-Lambkin2014; Apollonio Reference Apollonio, Philipps and Bero2016). A Cochrane review of interventions for tobacco utilise cessation among people in treatment for or recovery from substance use plant that offering pharmacotherapy for smoking abeyance increased tobacco forbearance (take chances ratio RR = 1.88, 95% CI 1.35–two.57), as did combined counselling and offer pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation (RR = 1.74, 95% CI 1.39–2.18) compared with usual care or no intervention. The review institute that tobacco cessation interventions were associated with smoking cessation for people in treatment for substance use (RR = 1.99, 95% CI 1.59–ii.50) and people in recovery (RR = 1.33, 95% CI 1.06–i.67), for people with alcohol dependence (RR = 1.47, 95% CI 1.20–1.81), and people with other drug dependencies (RR = i.85, 95% CI 1.43–2.40). Importantly, at that place was no prove that offering tobacco cessation interventions to people in drug dependence treatment or recovery afflicted abstinence from booze and other drugs (RR = 0.97, 95% CI 0.91–1.03).

How to discuss smoking without seeming didactic

Smoking cessation tin can exist a sensitive topic. Linking the person's smoking to their mental health issues and personal values tin assist to break downward the barriers to discussion (Miller Reference Miller and Rollnick2013). Information technology is important not to focus prematurely on smoking. Actively mind to the person's chief concerns (such as feelings of low). Introduce smoking by asking open-ended questions about any possible links betwixt smoking and their main business (due east.chiliad., mood): 'What links have you lot noticed between smoking and your moods?'. Seek permission to provide information near these links (e.g., 'I wonder if y'all'd be interested in hearing about recent research findings about how smoking affects mental health?'). It can also be useful to spend a few moments debunking the myths about smoking: 'A lot of people recollect that smoking is a stress reliever, only most people when they stop feel less stressed. Research shows their mental health improves'. After providing information (as outlined in this article), ask 'What practice y'all make of that?'. Explore with them their concerns virtually how smoking may be influencing their own mental health. Most people have other concerns most smoking, so enquire them, 'What other concerns do you have? What concerns you the most?'. So movement the person towards consideration of cessation by asking 'What'south the next step?'.

When people are not contemplating quitting in the foreseeable time to come, it can be worthwhile to open up the conversation upwards, acknowledging the pleasures initially experienced in the early days of smoking: 'Tell me some of the reasons y'all smoke'. Often people will reply that, although they did in one case enjoy being seen every bit 'cool' or function of the social crowd smoking while out drinking, such pleasures have long been outweighed past concerns such as addiction and price. Reflect on these concerns. If no concerns are mentioned, inquire 'Tell me what reasons y'all might have to want to quit?'. Here, the person's values may be raised, for example many people talk about wanting to be good parents, to exist effectually to see their children abound up and to be available for family members. Normalising the person's feelings can help, for example 'That's a common concern'. It is important to encourage the person and heave their confidence in their power to quit: 'Did you know that you can double your chances of quitting with assistance from our local cease smoking services?'. Once again it tin exist useful to spend a few moments debunking the myths near smoking: 'Can I tell y'all a few things about smoking that might surprise you and assistance you to quit?', 'I wonder, did you know that quitting smoking can improve your overall mental wellness?', 'Many people think its the nicotine in cigarettes that'southward harmful, but it'southward the components in the tobacco smoke that are the most harmful'.

Conclusions

Stopping smoking is one of the greatest changes that people can brand to better their health. However, smoking cessation tin can be a difficult topic to enhance, especially when a person's primary reason for consulting is their mental health or another wellness concern. Evidence suggests that smoking may cause some mental health problems and that the tobacco withdrawal cycle partly contributes to worse mental wellness. By stopping smoking, a person's mental health may improve, and the size of this improvement might be equal to that of taking antidepressants. By drawing on evidence-based methods such as behavioural back up and CBT, healthcare professionals can address smoking abeyance in a compassionate and respectful manner and successfully integrate smoking cessation treatment into routine care.

Author contributions

Chiliad.M.J.T. led on conceptualisation, investigation, writing the manuscript, reviewing and editing the manuscript and coordinating project administration. P.A. and Grand.R.Chiliad. supervised and mentored M.Chiliad.J.T. in writing the manuscript. P.A., A.L.B., D.S.K., M.R.M. and Due north.F. all contributed equally to conceptualisation, investigation, writing the manuscript, and reviewing and editing the manuscript. All authors contributed to the content of the manuscript.

Funding

G.Yard.J.T. is funded by a Cancer Research UK Population Researcher Postdoctoral Fellowship (C56067/A21330). A.L.B. is funded past a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Senior Research Fellowship (G1601524). P.A. is a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) senior investigator and is funded by NIHR Oxford's Biomedical Research Centre and Applied Research Centre. 1000.R.M. is a programme lead in the Medical Research Council Integrative Epidemiology Unit of measurement at the Academy of Bristol (MC_UU_00011/7).

Announcement of interest

G.M.J.T. and M.R.M. have previously received funding from Pfizer, who manufacture smoking cessation products. P.A. led a trial funded past the NIHR and GlaxoSmithKline donated nicotine patches to the NHS in support of the trial. A.Fifty.B. led trials funded by the NHMRC and GlaxoSmithKline donated nicotine replacement therapy in support of the trials.

ICMJE forms are in the supplementary textile, available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bja.2020.52.

MCQs

-

1 The all-time way to support smoking abeyance for people with common mental health bug is:

-

a to recommend that they try to quit once their mental health improves

-

b to recommend a combination of smoking cessation medicine and behavioural support for smoking cessation

-

c to propose that they use volition ability and nicotine replacement therapy

-

d to suggest that they become to their pharmacy for over-the-counter nicotine replacement therapy

-

east not to recommend smoking cessation, equally smoking tobacco offers stress relief.

-

-

2 In the 'very brief communication' approach to smoking cessation, the iii A's stand for:

-

a inquire, suggest, human activity

-

b avoid, propose, assist

-

c contend, advise, assistance

-

d inquire, appraise, assist

-

east aid, assess, suggest.

-

-

three After smoking a cigarette, tobacco withdrawal symptoms kickoff inside:

-

a 1 hours

-

b 24 hours

-

c twenty minutes

-

d 2–3 hours

-

e 12 hours.

-

-

four By and large, quitting smoking is associated with:

-

a worse mental health recovery

-

b disability to cope with symptoms of mental wellness problems

-

c long-term improvements in mutual mental wellness problems

-

d needing a higher dose of antidepressants

-

e none of the above.

-

-

v Smoking is a adventure factor in the development of:

-

a cancers and middle disease

-

b depression

-

c schizophrenia

-

d poor quality of life

-

e of the above.

-

MCQ answers

1 b 2 a three c 4 c five eastward

References

Abrantes, AM , Lee, CS , MacPherson, Fifty , et al. (2009) Health take a chance behaviors in relation to making a smoking quit endeavour amid adolescents. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 32: 142–9.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Apollonio, D , Philipps, R , Bero, L (2016) Interventions for tobacco use cessation in people in treatment for or recovery from substance utilise disorders. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 11: CD010274.Google ScholarPubMed

Aveyard, P , Begh, R , Parsons, A , et al. (2012) Brief opportunistic smoking abeyance interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis to compare advice to quit and offer of assistance. Addiction, 107: 1066–73.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Aveyard, P , Lewis, A , Tearne, Due south , et al. (2016) Screening and brief intervention for obesity in primary care: a parallel, two-arm, randomised trial. Lancet, 388: 2492–500.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Bakery, A , Kavanagh, D , Kay-Lambkin, F , et al. (2014) Randomized controlled trial of MICBT for co-existing alcohol misuse and depression: outcomes to 36-months. Periodical of Substance Abuse Treatment, 46: 281–90.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Baker, AL , Denham, AMJ , Pohlman, Southward , et al. (2019) Treating comorbid substance use and psychosis. In (eds Badcock, JC , Paulik, G ): 511–536. A Clinical Introduction to Psychosis: Foundations for Clinical Psychologists and Neuropsychologists. Academic Press.Google Scholar

Benowitz, NL , Hukkanen, J , Jacob, P (2009) Nicotine chemical science, metabolism, kinetics and biomarkers. In Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology (vol 192) (eds Henningfield, JE , London, ED , Pogun, S ). Springer.Google Scholar

Cooney, NL , Litt, MD , Cooney, JL , et al. (2007) Alcohol and tobacco abeyance in alcohol-dependent smokers: analysis of real-time reports. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 21: 277–86.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Doll, R , Peto, R , Boreham, J , et al. (2004) Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years' observations on male British doctors. BMJ, 328: 1519.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Gentry, South , Craig, J , Holland, R , et al. (2017) Smoking cessation for substance misusers: a systematic review of qualitative studies on participant and provider beliefs and perceptions. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 180: 178–92.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Guydish, J , Passalacqua, East , Pagano, A , et al. (2016) An international systematic review of smoking prevalence in addiction treatment. Addiction, 111: 220–30.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Haug, S , Schaub, MP , Schmid, H (2014) Predictors of adolescent smoking cessation and smoking reduction. Patient Pedagogy and Counseling, 95: 378–83.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Haug, Southward , Paz Castro, R , Kowatsch, T , et al. (2017) Efficacy of a technology-based, integrated smoking cessation and alcohol intervention for smoking cessation in adolescents: results of a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Journal of Substance Corruption Treatment, 82: 55–66.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Heather, North , Segal, G (2016) Overview of addiction as a disorder of choice and future prospects. In Habit and Choice: Rethinking the Relationship (eds Heather, N , Segal, G ): 463–82. Oxford University Press.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Hendricks, PS , Delucchi, KL , Humfleet, GL , et al. (2012) Alcohol and marijuana use in the context of tobacco dependence handling: impact on outcome and mediation of effect. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 14: 942–51.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Hitsman, B , Papandonatos, GD , McChargue, DE , et al. (2013) Past major depression and smoking cessation issue: a systematic review and meta-analysis update. Addiction, 108: 294–306.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Hughes, JR (2007a) Measurement of the effects of abstinence from tobacco: a qualitative review. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 21: 127–37.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Hughes, JR (2007b) Furnishings of abstinence from tobacco: valid symptoms and fourth dimension course. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, ix: 315–27.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Humfleet, G , Muñoz, R , Sees, K , et al. (1999) History of alcohol or drug problems, electric current apply of alcohol or marijuana, and success in quitting smoking. Addictive Behaviors, 24: 149–54.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Jamal, M , Does, AJ , Penninx, BW , et al. (2011) Age at smoking onset and the onset of depression and feet disorders. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 13: 809–19.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Jamal, Grand , AJ, Willem Van der Does , et al. (2012) Association of smoking and nicotine dependence with severity and form of symptoms in patients with depressive or feet disorder. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 126: 138–46.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Kay-Lambkin, F , Edwards, Southward , Baker, A , et al. (2013) The impact of tobacco smoking on treatment for comorbid depression and alcohol misuse. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 11 , 619–33.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Lapshin, O , Skinner, CJ , Finkelstein, J (2006) How do psychiatric patients perceive the side furnishings of their medications? German Journal of Psychiatry, ix: 74–nine.Google Scholar

Malone, V , Harrison, R , Daker-White, G (2018) Mental health service user and staff perspectives on tobacco addiction and smoking cessation: a meta-synthesis of published qualitative studies. Periodical of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 25: 270–82.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Mamede, Chiliad , Ishizu, K , Ueda, Chiliad , et al. (2007) Temporal change in human nicotinic acetylcholine receptor after smoking cessation: 5IA SPECT report. Journal of Nuclear Medicine, 48: 1829–35.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

McClure, EA , Bakery, NL , Hood, CO , et al. (2019) Cannabis and alcohol co-utilize in a smoking cessation pharmacotherapy trial for adolescents and emerging adults. Nicotine & Tobacco Research [Epub alee of impress] 15 October. Bachelor from: https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntz170.Google Scholar

McHugh, RK , Votaw, VR , Fulciniti, F , et al. (2017) Perceived barriers to smoking abeyance among adults with substance apply disorders. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 74: 48–53.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

McNeill, A , Brose, LS , Calder, R , et al. (2018) Testify Review of e-Cigarettes and Heated Tobacco Products 2018: A written report commissioned by Public Health England. Public Health England.Google Scholar

McNeill, A , Brose, LS , Calder, R , Bauld, L , Robson, D (2020) Vaping in England: an evidence update including mental wellness and pregnancy March 2020: a study commissioned by Public Wellness England. Public Health England.Google Scholar

Miller, WR , Rollnick, S (2013) Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change (third edn). Guilford Press.Google Scholar

National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Grooming (2019) Standard Treatment Programme: A Guide to Behavioural Support for Smoking Cessation. NCSCT.Google Scholar

National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training (2020) Very Brief Communication Training Module. National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training.Google Scholar

National Institute for Wellness and Intendance Excellence (2013) Smoking: Astute, Maternity and Mental Health Services (Public Health Guideline PH48). NICE.Google Scholar

National Plant for Health and Care Excellence (2018) Southwardtop Smoking Interventions and Services (Prissy Guideline NG92). NICE.Google Scholar

Pirie, One thousand , Peto, R , Reeves, GK , et al. (2013) The 21st century hazards of smoking and benefits of stopping: a prospective study of ane one thousand thousand women in the U.k.. Lancet, 381: 133–41.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Plana-Ripoll, O , Pedersen, CB , Agerbo, E , et al. (2019) A comprehensive analysis of mortality-related health metrics associated with mental disorders: a nationwide, register-based cohort written report. Lancet, 394: 1827–35.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Rabin, RA , Ashare, RL , Schnoll, RA , et al. (2016) Does cannabis apply moderate smoking cessation outcomes in treatment-seeking tobacco smokers? Analysis from a big multi-center trial. American Periodical on Addictions, 25: 291–6.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Richardson, S , McNeill, A , Brose, LS (2019) Smoking and quitting behaviours by mental health atmospheric condition in Smashing Britain (1993–2014). Addictive Behaviors, 90: 14–ix.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Royal College of Physicians, Imperial Higher of Psychiatrists (2013) Smoking and Mental Wellness: A Joint Report past the Royal Higher of Physicians and the Royal Higher of Psychiatrists. Royal Higher of Physicians.Google Scholar

Schauer, GL , King, BA , McAfee, TA (2017) Prevalence, correlates, and trends in tobacco employ and abeyance amongst current, one-time, and never adult marijuana users with a history of tobacco apply, 2005–2014. Addictive Behaviors, 73: 165–71.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Segan, CJ , Bakery, AL , Turner, A , et al. (2017) Nicotine withdrawal, relapse of mental illness, or medication side-effect? Implementing a monitoring tool for people with mental illness into quitline counseling. Periodical of Dual Diagnosis, thirteen: 60–6.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Sheals, K , Tombor, I , McNeill, A , Shahab, L (2016) A mixed-method systematic review and meta-analysis of mental health professionals' attitudes toward smoking and smoking cessation among people with mental illnesses. Addiction, 111(9): 1536–1553.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Stevenson, JG , Oliver, JA , Hallyburton, MB , et al. (2017) Smoking environment cues reduce ability to resist smoking as measured by a delay to smoking chore. Addictive Behaviors, 67: 49–52.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Taylor, GMJ , McNeill, A , Girling, A , et al. (2014) Change in mental health after smoking abeyance: systematic review and meta-assay. BMJ, 348: g1151.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Taylor, GMJ , Munafò, MR (2019a) Does smoking cause poor mental health? Lancet Psychiatry, half dozen: ii–three.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Taylor, GMJ , Aveyard, P , Bartlem, One thousand , et al. (2019b) IntEgrating Smoking Cessation treatment as function of usual Psychological care for low and anxiety (ESCAPE): protocol for a randomised and controlled, multicentre, acceptability, feasibility and implementation trial. Pilot and Feasibility Studies, 5: 16.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Taylor, GMJ , Itani, T , Thomas, KH , et al. (2020a) Prescribing prevalence, effectiveness, and mental health prophylactic of smoking cessation medicines in patients with mental disorders. Nicotine & Tobacco Enquiry, 22: 48–57.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Taylor, GMJ , Sawyer, Chiliad , Kessler, D , et al. (2020b) Views about integrating smoking abeyance treatment within psychological services for patients with common mental illness: a multi-perspective qualitative study. medRxiv [Preprint]. Bachelor from: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.18.20024596.Google Scholar

Van Zundert, RMP , Kuntsche, E , Engels, RCME (2012) In the heat of the moment: alcohol consumption and smoking lapse and relapse amid adolescents who have quit smoking. Drug and Booze Dependence, 126: 200–5.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Vermeulen, JM , Wootton, RE , Treur, JL , et al. (2019) Smoking and the hazard for bipolar disorder: Evidence from a bidirectional Mendelian randomisation study. The British Periodical of Psychiatry [Epub ahead of print] 17 Sep 2019. Available from: https://doi.org/ten.1192/bjp.2019.202.Google Scholar

Verplaetse, TL , McKee, SA (2017) An overview of alcohol and tobacco/nicotine interactions in the man laboratory. American Journal of Drug and Booze Abuse, 43: 186–96.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Vogel, EA , Rubinstein, ML , Prochaska, JJ , et al. (2018) Associations between marijuana use and tobacco abeyance outcomes in young adults. Periodical of Substance Abuse Treatment, 94: 69–73.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Weinberger, AH , Gbedemah, Chiliad , Goodwin, RD (2017) Cigarette smoking quit rates among adults with and without alcohol use disorders and heavy alcohol use, 2002–2015: a representative sample of the United States population. Drug and Booze Dependence, 180: 204–vii.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Weinberger, AH , Platt, J , Copeland, J , et al. (2018) Is cannabis use associated with increased take a chance of cigarette smoking initiation, persistence, and relapse? longitudinal information from a representative sample of The states adults. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 79(2): 17m11522.Google ScholarPubMed

World Health Organisation (2011) WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic: Warning about the Dangers of Tobacco.Google Scholar

Wu, LT , Anthony, JC (1999) Tobacco smoking and depressed mood in late childhood and early adolescence. American Journal of Public Health, 89: 1837–twoscore.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

Source: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/bjpsych-advances/article/addressing-concerns-about-smoking-cessation-and-mental-health-theoretical-review-and-practical-guide-for-healthcare-professionals/8E6C7321AF40D6AA254149A1888F28CF

0 Response to "Change in Mental Health After Smoking Cessation Systematic Review and Meta-analysis"

ارسال یک نظر